Sorokin, who began writing in the 80's, was initially part of the conceptualists or "sots-artists," a group of mostly visual artists who sought to undermine Russia's sacred myths. In recent years, his (increasingly grotesque) writing has taken, among other things, 21st-century nationalism as its target. These books are not for the faint of heart, but if you are like me, you will want to keep reading out of respect for his audacity. If violence, explicit language, or brutal iconoclasm makes you uncomfortable, you should probably stay away from Sorokin's prose.

Sorokin, who began writing in the 80's, was initially part of the conceptualists or "sots-artists," a group of mostly visual artists who sought to undermine Russia's sacred myths. In recent years, his (increasingly grotesque) writing has taken, among other things, 21st-century nationalism as its target. These books are not for the faint of heart, but if you are like me, you will want to keep reading out of respect for his audacity. If violence, explicit language, or brutal iconoclasm makes you uncomfortable, you should probably stay away from Sorokin's prose.

Wednesday, July 13, 2011

Sorokin after Sots-Art

The July issue of Open Letters Monthly has some great summer reading recommendations, and includes my thoughts on on Jamey Gambrell's translations of Vladimir Sorokin's Day of the Oprichnik and the Ice Trilogy.

Sorokin, who began writing in the 80's, was initially part of the conceptualists or "sots-artists," a group of mostly visual artists who sought to undermine Russia's sacred myths. In recent years, his (increasingly grotesque) writing has taken, among other things, 21st-century nationalism as its target. These books are not for the faint of heart, but if you are like me, you will want to keep reading out of respect for his audacity. If violence, explicit language, or brutal iconoclasm makes you uncomfortable, you should probably stay away from Sorokin's prose.

Sorokin, who began writing in the 80's, was initially part of the conceptualists or "sots-artists," a group of mostly visual artists who sought to undermine Russia's sacred myths. In recent years, his (increasingly grotesque) writing has taken, among other things, 21st-century nationalism as its target. These books are not for the faint of heart, but if you are like me, you will want to keep reading out of respect for his audacity. If violence, explicit language, or brutal iconoclasm makes you uncomfortable, you should probably stay away from Sorokin's prose.

Sorokin, who began writing in the 80's, was initially part of the conceptualists or "sots-artists," a group of mostly visual artists who sought to undermine Russia's sacred myths. In recent years, his (increasingly grotesque) writing has taken, among other things, 21st-century nationalism as its target. These books are not for the faint of heart, but if you are like me, you will want to keep reading out of respect for his audacity. If violence, explicit language, or brutal iconoclasm makes you uncomfortable, you should probably stay away from Sorokin's prose.

Sorokin, who began writing in the 80's, was initially part of the conceptualists or "sots-artists," a group of mostly visual artists who sought to undermine Russia's sacred myths. In recent years, his (increasingly grotesque) writing has taken, among other things, 21st-century nationalism as its target. These books are not for the faint of heart, but if you are like me, you will want to keep reading out of respect for his audacity. If violence, explicit language, or brutal iconoclasm makes you uncomfortable, you should probably stay away from Sorokin's prose.

Friday, February 25, 2011

our perestroikas

Last week my dear friend and colleague Natalia Roudakova went to Russia for a conference, so I got to show Robin Hessman's 2010 My Perestroika to her undergraduate "authoritarianisms" class. Hessman had lived in Russia in the 1990s, working as the producer for the Russian Sesame Street. This film was about Russians her own age:

Just coming of age when Gorbachev appeared, they were figuring out their own identities as the very foundations of their society were being questioned for the first time. And then they graduated just as the USSR collapsed and they had to figure out a completely new life as young adults, with no models to follow. (-Hessman)

Hessman was strangely absent from her own film, but the way her subjects spoke to the camera evoked a distant addressee, as though they were sharing their experience with someone who would never really know the full story, but whose relationship to them mattered. Did perestroika itself, the viewer might wonder, with its lines for MacDonalds, its blue-jeans, its Pepsi Cola, also have an absent American addressee? Maybe this phantom-like American presence is why the film made me think of my perestroika. I turned fourteen in 1989, and my bedroom was plastered with Soviet gymnasts: Yelena Shushunova, Dmitri Bilozerchev, Svetlana Boginskaia. That year I started taking Russian. A few months later Nadia Comaneci defected from Rumania and the Berlin wall fell. In 1991 I came home from Russian camp, newly enamored of Russian folk songs, a couple of weeks before the putsch that put Yeltsin in power. This coincidence of my personal passions with the riveting geopolitical changes of the early 90's is probably why I stayed in Russian, long after I left gymnastics and choir for other hobbies. And yet I went through high school with the Scorpions' "Wind of Change" playing as background music, but didn't stop to think about the words until years later, when I listened to someone in Ukraine play it on a guitar and sing it in broken English.

Hessman was strangely absent from her own film, but the way her subjects spoke to the camera evoked a distant addressee, as though they were sharing their experience with someone who would never really know the full story, but whose relationship to them mattered. Did perestroika itself, the viewer might wonder, with its lines for MacDonalds, its blue-jeans, its Pepsi Cola, also have an absent American addressee? Maybe this phantom-like American presence is why the film made me think of my perestroika. I turned fourteen in 1989, and my bedroom was plastered with Soviet gymnasts: Yelena Shushunova, Dmitri Bilozerchev, Svetlana Boginskaia. That year I started taking Russian. A few months later Nadia Comaneci defected from Rumania and the Berlin wall fell. In 1991 I came home from Russian camp, newly enamored of Russian folk songs, a couple of weeks before the putsch that put Yeltsin in power. This coincidence of my personal passions with the riveting geopolitical changes of the early 90's is probably why I stayed in Russian, long after I left gymnastics and choir for other hobbies. And yet I went through high school with the Scorpions' "Wind of Change" playing as background music, but didn't stop to think about the words until years later, when I listened to someone in Ukraine play it on a guitar and sing it in broken English.

When the film was over I looked out at Natalia's students and realized that most of them were born after 1991. They have as little a recollection of Gorbachev's Soviet Union as I do of Nixon's presidency. Chances are good, though, that they, and I, will look back at 2011 as a defining moment, a moment that tied our lives to the enormous, shifting, global politics around us, a moment we lived through but will not have the space to assess for a long time. The other day Mikhail Gorbachev wrote an Op-Ed in the New York Times that suggested he is, two decades later, still assessing his perestroika, and still holding out hope:

Looking at those faces, one wants to believe that Egypt's democratic transition will succeed. That would be a good example, one the entire world needs.

Just coming of age when Gorbachev appeared, they were figuring out their own identities as the very foundations of their society were being questioned for the first time. And then they graduated just as the USSR collapsed and they had to figure out a completely new life as young adults, with no models to follow. (-Hessman)

Hessman was strangely absent from her own film, but the way her subjects spoke to the camera evoked a distant addressee, as though they were sharing their experience with someone who would never really know the full story, but whose relationship to them mattered. Did perestroika itself, the viewer might wonder, with its lines for MacDonalds, its blue-jeans, its Pepsi Cola, also have an absent American addressee? Maybe this phantom-like American presence is why the film made me think of my perestroika. I turned fourteen in 1989, and my bedroom was plastered with Soviet gymnasts: Yelena Shushunova, Dmitri Bilozerchev, Svetlana Boginskaia. That year I started taking Russian. A few months later Nadia Comaneci defected from Rumania and the Berlin wall fell. In 1991 I came home from Russian camp, newly enamored of Russian folk songs, a couple of weeks before the putsch that put Yeltsin in power. This coincidence of my personal passions with the riveting geopolitical changes of the early 90's is probably why I stayed in Russian, long after I left gymnastics and choir for other hobbies. And yet I went through high school with the Scorpions' "Wind of Change" playing as background music, but didn't stop to think about the words until years later, when I listened to someone in Ukraine play it on a guitar and sing it in broken English.

Hessman was strangely absent from her own film, but the way her subjects spoke to the camera evoked a distant addressee, as though they were sharing their experience with someone who would never really know the full story, but whose relationship to them mattered. Did perestroika itself, the viewer might wonder, with its lines for MacDonalds, its blue-jeans, its Pepsi Cola, also have an absent American addressee? Maybe this phantom-like American presence is why the film made me think of my perestroika. I turned fourteen in 1989, and my bedroom was plastered with Soviet gymnasts: Yelena Shushunova, Dmitri Bilozerchev, Svetlana Boginskaia. That year I started taking Russian. A few months later Nadia Comaneci defected from Rumania and the Berlin wall fell. In 1991 I came home from Russian camp, newly enamored of Russian folk songs, a couple of weeks before the putsch that put Yeltsin in power. This coincidence of my personal passions with the riveting geopolitical changes of the early 90's is probably why I stayed in Russian, long after I left gymnastics and choir for other hobbies. And yet I went through high school with the Scorpions' "Wind of Change" playing as background music, but didn't stop to think about the words until years later, when I listened to someone in Ukraine play it on a guitar and sing it in broken English.When the film was over I looked out at Natalia's students and realized that most of them were born after 1991. They have as little a recollection of Gorbachev's Soviet Union as I do of Nixon's presidency. Chances are good, though, that they, and I, will look back at 2011 as a defining moment, a moment that tied our lives to the enormous, shifting, global politics around us, a moment we lived through but will not have the space to assess for a long time. The other day Mikhail Gorbachev wrote an Op-Ed in the New York Times that suggested he is, two decades later, still assessing his perestroika, and still holding out hope:

Looking at those faces, one wants to believe that Egypt's democratic transition will succeed. That would be a good example, one the entire world needs.

Friday, February 11, 2011

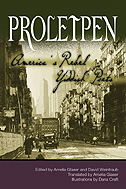

proletpen, the rock-opera

Friends, readers, musicians in search of lyrics! Forgive the descent into self-promotion, but I have just gotten word from University of Wisconsin Press that Proletpen, America's Rebel Yiddish Poets will be offered in its attractive hardcover edition at only $26.99, down from its earlier $45 (it can also be purchased electronically for $16.95). I translated the 100 poems in this volume while I was in graduate school, and edited it together with David Weintraub of the Dora Teitelboim Foundation. The book is bilingual. It also features woodcuts by the illustrator Dana Craft. The historical introduction is by Dovid Katz whose father, the poet Meynke Katz, features prominently in the volume. Most of the poems here are from the 1930s, and most of the poets were fellow travelers (if not members) of the CPUSA, which means that there are love songs here to Lenin and red flags. But there are also love songs to people, and sad songs about war and the unforgiving city landscape.

Friends, readers, musicians in search of lyrics! Forgive the descent into self-promotion, but I have just gotten word from University of Wisconsin Press that Proletpen, America's Rebel Yiddish Poets will be offered in its attractive hardcover edition at only $26.99, down from its earlier $45 (it can also be purchased electronically for $16.95). I translated the 100 poems in this volume while I was in graduate school, and edited it together with David Weintraub of the Dora Teitelboim Foundation. The book is bilingual. It also features woodcuts by the illustrator Dana Craft. The historical introduction is by Dovid Katz whose father, the poet Meynke Katz, features prominently in the volume. Most of the poems here are from the 1930s, and most of the poets were fellow travelers (if not members) of the CPUSA, which means that there are love songs here to Lenin and red flags. But there are also love songs to people, and sad songs about war and the unforgiving city landscape.

The sentiments in these poems range from political alignment with leaders like Julio Melo and Anna Pauker to vitriolic criticism of the Party. In the five years since the book came out, I have come to see them as emotional documents that give us the tiniest glimpse into the fury of a strange, and often forgotten, episode in American history.

I have a fantasy that a musician will pick up this volume and put together an indie rock album based on these poems. Klezmer would also do nicely.

Monday, February 7, 2011

my enchanted contemporary

The same year I was born in California, Ëzhik was born in Moscow. Yury Norshteyn created him out of 2-dimensional cut-outs, entrusted him with a jar of raspberry jam, and lowered him into a foggy night. The little hedgehog embarks on a journey and gets terrifyingly, blissfully, lost. He encounters danger, love, regret, exhilaration, hopelessness, and finally, a peaceful acceptance of his fate, which (spoiler alert) carries him safely to his destination. I'm never sure when it will happen, but about once a year I pass through a week or two when I must watch Ëжик в тумане every night before falling asleep, in hopes, I guess, of dreaming about a white horse or a very tall oak.

Thursday, January 27, 2011

Ночь, улица, фонарь

I found this ad for Russia's MTS cell phone company on a search for Aleksandr Blok's 1912 "Ночь, улица, фонарь, аптека," and it warmed my Russophile heart. Here is the full poem:

-

Ночь, улица, фонарь, аптека,

Бессмысленный и тусклый свет.

Живи еще хоть четверть века-

Все будет так. Исхода нет.

Умрешь - начнешь опять сначала

И повторится все, как встарь:

Ночь, ледяная рябь канала,

Аптека, улица, фонарь.

I have taken much license with my translation:

A night, a street, a streetlamp, drugstore,

Unthinkable and fading light.

Live but a quarter century more:

Nothing will change. There's no way out.

You'll die then start from the beginning,

All the old patterns will repeat:

The night, the canal's icy rippling,

The drugstore, streetlamp, and the street.

The ad wouldn't work if 99% of it's viewers hadn't once been made to memorize this poem. A man is dictating Blok's famous words into his mobile phone, and the words float out into the night, finding their reflections in posters and ads around the city. But the resolution is tragic: the addressee is a student with a casually hidden ear bud. Instead of memorizing the poem, he has the technology to find it on the same streets that inspired Blok. Blok's poem will probably disappear from the storehouses of his readers' minds; but the lonely quotidian of a winter city night will remain. A night... a street... a cellphone... drugstore.

Thursday, January 20, 2011

eyes on eyes

St. Jerome called the face the "mirror of the mind." But Lev Kuleshov taught us that the mind being mirrored isn't necessarily the one attached to the face, but rather the one attached to the person observing and interpreting that particular face's expressions. In a short sequence from 1917-18, Kuleshov spliced close-ups of the popular character actor Ivan Mozzhukhin staring intently into the camera with alternating images of a bowl of soup, a child in a coffin, and a beautiful woman. The audience was thrilled by his portrayals of hunger, sadness, and lust: they didn't notice that the same footage of Mozzhukhin was repeated over and over. (The only version of this on the internet includes Spanish subtitles -- gracias to those who made it available!)

A few years earlier Mozzhukhin had played the devil in Starevich's 1913 adaptation of Gogol's "Night Before Christmas." Here is a Kuleshov test you can take at home: in this frame, is he:

a. hungry for a bowl of soup?

b. terrified that he will be beaten by an upstanding blacksmith?

c. craftily plotting to snatch the moon from the sky?

or d. with some careful montage, any of the above?

When I taught my Soviet film class in 2010, one of my students, Amanda Goodman, created her own Kuleshov experiment to successful effect. Rather than alternating between hunger, sadness, and lust, Amanda's protagonist is pictured observing a strip tease with apparently increasing interest. Her films have already screened at in the Sixth College UCSD Film Festival. Keep an eye out for this creative eye.

Friday, January 7, 2011

New Year's Furry Things

Youtube videos probably say at least as much about the late-night viewer as they do about the producer. This particular viewer is not quite ready to embrace her own strange fascination with Chai Vdvoem's New Year's furry things, the slender woman-with-a-key who rises like a yolochka toward her flat-screen TV, or the gogolian pig-demon the woman's lover for some reason sees fit to present her with. (Notice how the poor pig sniffs around the presents as if looking for a lost sleeve.) But I am posting this anyway, a placeholder for deeper thoughts on overturn... or at least a warm, fuzzy tribute to mandarin oranges and desire.

Netflix Files: The Man Who Cried

As far as I’m concerned there are 3 reasons one might spend a regrettable evening watching this movie. The first is Golijov's rather nice original score. The second is a brief sound cameo featuring my friend Jeremy exclaiming something in Yiddish from off-screen. The third is Cate Blanchett's wonderful, if somewhat anachronistic, portrayal of a Russian émigré. Blanchett's character is a masterful combination of desperate seductress, anti-Semite, and faithful friend. All of the other characters in the film are stiff, frankly offensive, caricatures. Christina Ricci who, miraculously rescued from a pogrom must sing her way to America to find her father (Oleg Yankovsky), plays a less human version of Feivel the Mouse from "An American Tale." Ms. Ricci, whose childhood alter ego is played by an undeniably cute Claudia Lander-Duke, utters a handful of lines throughout the entire film; what she does say is spoken without the least hint of expression. The doe-eyed gazes that the actress employed so brilliantly in Buffalo’66 simply do not work for this character. Johnny Depp's role as a gypsy horse-trainer is the stuff of bad porn. For a film with the word "cried" in the title, with the exception of Blanchett's aging Russian ballerina and the diva-breakdowns of John Turturro's fascist opera singer, any attempts at emotion are either misplaced, or simply unconvincing.

From the Netflix files: Russian Ark

Don't watch The Russian Ark [Russkii Kovcheg] (2002) for the plot (there isn’t a plot), or for the costumes (some appear to have been stolen from tourist-photo-op-actors on Nevsky). But Aleksandr Sokurov’s virtuosic single shot is pleasantly dizzying, and marks an important innovation in the cinematic portrayal of time and space. The entire film can be boiled down to the following: a whispering Marquis de Custine (Sergei Dreiden) with an unidentifiable European accent guides the viewer in an hour-and-a-half-long polonaise through various chapters of Russian history. By setting the entire film in St. Petersburg’s splendid Hermitage (the permission for which marks a heroic achievement in its own right), Sokurov likens his contemporary audience’s distant perception of history to a tourist’s first picturesque walk through a winter garden in bloom.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)